In his notorious debate with Gordon, Bennett Reimer (1994) was right, sort of. He chastised Gordon for focusing too heavily on songs and patterns to the almost total exclusion of—how shall I describe them?—masterpieces. He was wrong to suggest that MLT must work this way, but I think he discerned a disturbing trend. All MLTers agree that functional, contextual patterns are the indispensible “part” of whole-part-whole. But rote songs? In at least one respect, I’m different from my MLT colleagues. I never drank the rote song Kool-Aid.

Darrel Walters described functional tonal and rhythm patterns as the “vitamins” of musical content. His comparison is apt as far as it goes, but let’s push it along. Patterns are vitamin pills; Beethoven Symphonies are nutritious meals, exquisitely prepared. What about teacher-composed songs and chants? I think of them as meal replacement bars. They provide temporary nutrition, vitamins, fiber; they’re better than nothing, and they fill you up on long road trips. But human-made, synthesized nutrition bars cannot, in the long term, replace real, natural food. Let’s not pretend they can.

And the same is true for teacher-composed songs.

I don’t believe my students have adequately learned to audiate minor tonality just because they’ve learned functional patterns along with a few rinky-dink rote songs in the minor mode I made up in my car while driving to work.

Like this one …

Tchaikovsky was one of the greatest melodists of all time. But you’d never know it by listening to my bastardization of his melody from Swan Lake. So that you may compare the two, here is Tchaikovsky’s melody in its original form:

On the plus side, my tune checks all the boxes: The range (from C sharp to B natural) is narrow enough that kindergarten through 2nd grade children can sing the song easily while they rock front and back; the phrase structure is a serviceable parallel period in the minor mode.

And what was my “inspiration”? I needed a front-and-back rocking song in minor/triple. It’s that simple. So I thought about it for 5 minutes, remembered this tune by Tchaikovsky, simplified it (by removing the exquisite hemiola rhythms in the woodwinds), threw in some descriptive lyrics, and there you have it. Yes, the “Front and Back” song serves educational purposes—tonal, metric, kinesthetic—and serves them well. And yet for all that, my tune (in contrast to Tchaikovsky’s) is rinky-dink rubbish.

TRADITIONAL MLTer: I’m assuming, Eric, that you’ve composed many songs for your students, especially those in Kindergarten. Do you really want to call your compositions “rinky-dink?” Why put yourself down that way? And why are you so skeptical about the value of rote songs? Simply sing the “Front and Back” song with students while engaging with them in the movement activity; then teach functional patterns in the context of minor, and then return to the rote song by asking students to sing the resting tone. There’s your whole-part-whole process. Students are audiating the minor mode. A job well done. Finished.

To which I respond with a full-throated no! My students have not arrived at the final whole, just because they can name the tonality of my song or sing its resting tone. Despite the MLT predilection to isolate musical elements from each other, tonality does not exist in a vacuum. How we audiate patterns in major tonality (in Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, for instance) is pushed and pulled by the musical elements that surround those patterns.

Let me show you what I mean. What follows is a deep dive into the development section of Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, 1st movement. Before we go toe to toe with Beethoven, I want to clarify a few things: We can’t expect our pre-school or lower elementary students to understand a Beethoven Symphony with the same depth that high school or college students can bring to it; but surely, we don’t expect our students to remain at the acculturation stage of preparatory audiation. As students emerge from babble, and understand music better, they need greater musical “nourishment” than rote songs and patterns can provide. In my units on Genre, tempo, vocal register, and Dynamics, you can find dozens of sound files and lessons that take elementary students far beyond acculturation. Eventually—as you’ll see in the next section—students will be able to audiate complex musical ambiguities not found in short, monophonic rote songs.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Bernstein Analyzes Beethoven

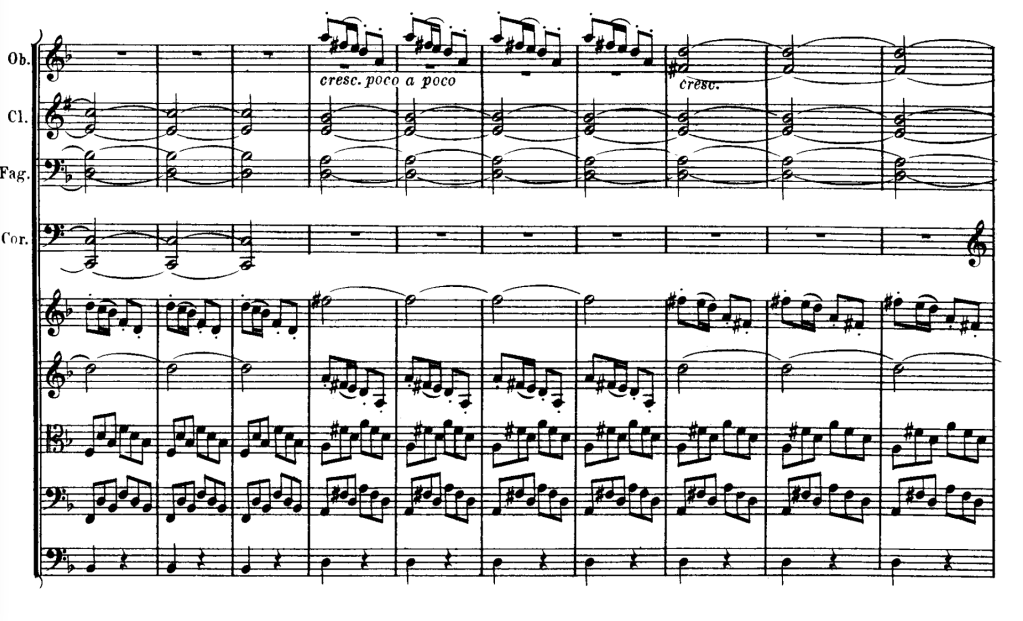

In his lecture series, The Unanswered Question, Bernstein (1976) discussed the following 24-bar passage from Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, 1st movement, mm. 151-174.

FIGURE 1. Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, 1st movement, measure 151-174

No one can explain musical ambiguity in Beethoven as well as Bernstein, so I will yield the floor to him (with a few abridgments). Before I let Bernstein go on at length, I must mention two things: First, Bernstein’s descriptions, though fascinating, are a bit hard to follow, so I’ve created Tables 1 and 2 below to help clarify his analysis. Second, in his discussion, Bernstein refers to the following repetitive motive (shown in Figure 2) as the “jaunty” motive.

FIGURE 2: The “Jaunty” Motive

Bernstein (1976, pp. 179-84) wrote:

What are we to say of the long strings of unvaried repetition [in this] development section? The profuse repetition could be a metaphor for the profuse repetition of Nature herself, the infinite reduplication of species. But [this is] not the kind of metaphor we are seeking. What is the musical metaphor to be discovered in that famous long passage of literal repeats? We will look at measures 151-174, the first 24 bars in a larger 92 bar structure. What is their metaphorical meaning—not in terms of jonquils and daisies, but of notes and rhythms? We know that the notes come from the “jaunty” motive, transposed to B-flat major, and played 4 times by the 1st violins. This is then literally repeated by the 2nd violins, doubled by [an oboe or flute] an octave higher. That makes 8 bars. The 8-bar segment is repeated and re-repeated with the same alternations of 1st violins as against 2nd violins plus a high woodwind; and it’s played 3 times in all—3 times 8 bars making 24 bars. That’s one way of looking at this episode, from an orchestral point of view. We perceive one of Beethoven’s intentions via his instrumental texture, the alternating high and low registers, and the 24-bar crescendo to a climax.

In Table 1, I show what the 24 bars reveal from an orchestral point of view:

Table 1.

Bernstein (1976, pp. 184-86) goes on to say that listeners may hear (audiate, in other words) this same passage in a completely different way.

Now let’s view the same 24 bars harmonically, and we find a very different story. Four bars of B-flat in the 1st violins, as before, repeated as before in the 2nd violins with the higher woodwind octave. Again [we hear] the 1st violins—that’s now 12 bars. And now a sudden switch of key to D major (bar 163) for 12 more bars. We’re still following the same instrumental pattern, mind you, but in this new key of D, which is maintained for 2 more repeats, finally [we arrive at the] climax. This has been a totally different construction of those same 24 bars—2 x 12: twelve bars in B-flat and 12 bars in D. Not at all 3 x 8, as we saw at first. In other words, there are 2 different substructures functioning simultaneously within the span of 24 bars. One substructure is the orchestral texture, 3 x 8; and the other is the harmonic rhythm, 2 x 12. And the simultaneous contradiction of the two creates one glorious ambiguity…out of what seemed to be merely 24 stupefying repetitions.

In Table 2 below, I offer a side-by-side description of the 2 ways to audiate Beethoven’s 24-bar passage.

Table 2:

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Audiating Both/And and Not Merely Either/Or

What did Bernstein and Beethoven reveal? Two things. First, a single phrase of music may embody different phrase structures. And second (and even more important for this discussion), conflicting musical elements can be equally true, and mutually supportive. Could it be that great works of music, works that have moved people across cultures and centuries, hold our interest because of the push and pull of built-in ambiguities? I believe so. But, I hear you asking, what about works of music that do not have conflicting elements? Can a single element in a piece of music be ambiguous? Can a monophonic melody be, for instance, tonally ambiguous?

Let’s have some fun with the “Star-Spangled Banner.” Is the opening melody (minus the harmony) in the major or lydian mode?

Yes, I concede: You can reasonably audiate this melody in either major or lydian. But notice that the ambiguity in this case is either/or. Never would a musician audiate the “Star-Spangled Banner” in major and lydian at the same time. You choose one tonality to audiate, reject the other, and stick with your choice.

In contrast, the Bernstein/Beethoven example above is a both/and ambiguity, and by that I mean the following: 1) orchestration and keyality are equally valid ways to understand Beethoven’s phrase structure; 2) those two elements, though they seem to conflict, are interactive; and 3) their interaction is aesthetically gripping precisely because they vie for our attention.

How does all this fit with Gordon’s stages of audiation? At Gordon’s 4th stage of audiation, we reassess our first impressions of the tonality, keyality, meter, and form of a piece of music—but when we do so, we focus on one element at a time. At stage 5, we compare one piece with another, but we still focus on a single element, tonality perhaps. One glaring omission in Gordon’s theories is that he never accounted for musical elements working in tandem. Could there be a stage of audiation, one that Gordon did not consider, in which we audiate two or more elements that conflict with each other, but are equally compelling and, on a deep level, mutually supportive (as in the Beethoven example above)? I think so, and I’ll write more about it soon in a future blog post: Form, Flux, and a New Stage of Audiation.)

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Conclusion

And now I can loop back around to why rote songs are not enough. Rote songs serve music education in the short-term (like a protein meal-replacement bar), but they’re inadequate for our students’ musical “nutrition” in the long-term. It’s not just because Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony is a masterpiece, while Bluestine’s “Front and Back” song is a far cry from one. Beethoven surrounded his major tonality with keyality, form, timbre, texture, phrasing, dynamics, rhythm patterns, tempo, and meter. And those elements may conflict with each other, the way orchestration and harmonic rhythm were in conflict in the passage Bernstein analyzed; and such conflict—orchestration telling us one thing, harmonic rhythm telling us something else— is what makes a piece worthy of serious study.

In teacher-composed songs there are rarely either/or conflicts, and never both/and conflicts. My composed songs—typically short, monophonic melodies—feature musical elements that neither contradict each other, nor develop over long periods of time. Under these conditions (and restrictions), conflicts and ambiguities simply cannot arise.

And if students never grapple with musical ambiguities, they will never deeply understand the final whole of whole-part-whole. What’s more, our students will not learn to understand pieces beyond Stage 4 and 5 of audiation. Instead, they will be trapped in a musical world where elements develop in isolation, never in tandem. To sum up, if we expose our students to nothing but patterns and short songs, we stunt their musical growth, and forfeit the key music education goal of teaching students to audiate multifaceted works.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Bernstein, L. (1976). The unanswered question: Six talks at Harvard. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Reimer, Bennett and Gordon, Edwin. (1994). “The Reimer/Gordon Debate on Music Learning: Complementary or Contradictory Views?” MENC National Biennial In-service Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio. Audio Tape Stock #3004, ISBN 1-56545-052-3