From Partial Synthesis to Chaining/Compressing

What’s wrong with the name “partial synthesis”?

Twenty-three years ago, I wrote that MLTers should change the name “partial synthesis” to something else. I gave three reasons. First, it scares music teachers new to MLT, turns them off to it, makes them feel stupid, drives them away. Second, it reveals nothing, because every level in the skill-learning sequence is partial, and every level is a synthesis. And third, it fails to reveal what actually happens at this skill level.

While we’re on the subject, what does happen at this skill level? MLTers are likely to give an answer something like the following, which appears on the GIML website:

At the aural/oral and verbal association levels, students learn tonal and rhythm patterns individually. Although the teacher always establishes tonal or rhythm context, syntactical relationships among patterns are not emphasized. At partial synthesis, students learn to give syntax to a series of tonal or rhythm patterns. The teacher performs a series of familiar tonal or rhythm patterns without solfege and without first establishing tonality, and students are able to identify the tonality or meter of the series. The purpose is to assist them in recognizing for themselves familiar tonalities and meters. As a result of acquiring partial synthesis skill, a student is able to listen to music in a sophisticated, musically intelligent manner.

I like this explanation; and, in fact, you’ll find something similar in my book (2000). I suggested we use the word “chaining,” a term Robert Gagne used in his book The Conditions of Learning (1965). (The term “verbal association” also comes from Gagne.) In his hierarchy of the various types of learning, Gagne describes the process of chaining this way: “[Children] respond to multiple stimuli in a sequence that accomplishes a more complex task than encountered in stimulus/response learning.”

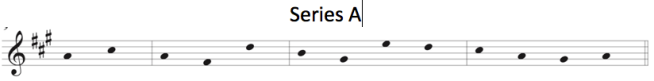

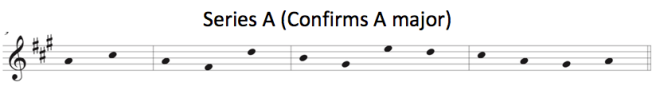

I wrote (2000) that “chaining,” in musical terms, means that tonal or rhythm patterns in a series reveal a tonality or meter; individual patterns do not.

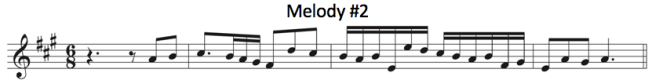

So why not just call this level “chaining,” or perhaps “contextualization,” a term MLTer Andy Mullen put forth?[i] Because these words are not enough; they give us only half the story. They’re all about the context each series of patterns reveals: major tonality, duple meter, etc., which is fine, as a start. But at this level, students learn a subtler skill: how to compress a long, unwieldy piece of music into shorter forms that are both pliant and bare-boned — series of tonal and rhythm patterns. (If you’d like more information about this, please consult my book The Ways Children Learn Music, pp. 131-141.)

So then. The word “chaining” is good but incomplete. It gets at the what — the context embodied in a series of patterns. But it doesn’t explain the how: the process of shrinking music down to a series of patterns.

What’s wrong with the term “contextualization”? It has the word “context” in it, I hear you saying, so people should understand its meaning right away. “Chaining” calls for an explanation; “contextualization” speaks for itself. But is this really true? Let’s take a closer look at the two options — chaining and contextualization.

I imagine the following 2 scenes:

_________________________________________________________________________________________

SCENE 1: A new MLTer asks what “chaining” means.

NEW MLTer: I get what happens at the aural/oral and verbal association levels. What’s the next level?

OLD-TIME MLTer: Chaining.

NEW MLTer: Chaining? What does that mean? I get that kids sing and chant individual patterns during the aural/oral and verbal association levels. But at those lower levels, don’t several students create a chain of patterns when the teacher calls on one student after another to sing? Chaining happens at those lower levels too, doesn’t it?

OLD-TIME MLTer: Yes, but at this level, the various series, or “chains” of tonal or rhythm patterns have syntactic meaning they would not have if you sang or chanted them in isolation. That’s why, at this level, you don’t have to establish tonality or meter at the outset of the LSA, and you don’t have to sing or chant with syllables. The series of patterns itself reveals the tonal or metrical context.

SCENE 2: A new MLTer asks what “contextualization” means.

NEW MLTer: I get what happens at the aural/oral and verbal association levels. What’s the next level?

OLD-TIME MLTer: Contextualization.

NEW MLTer: Contextualization? What does that mean? I get that kids sing and chant individual patterns during the aural/oral and verbal association levels. But doesn’t the teacher establish the tonal and metrical context at the outset of each LSA? And doesn’t the teacher continue to reestablish tonality and meter throughout the LSA? Contextualization happens at those lower levels too, doesn’t it?

OLD-TIME MLTer: Yes, but at this level, the various series of tonal or rhythm patterns are contextualized. They have syntactic meaning they would not have if you sang or chanted them in isolation. That’s why, at this level, you don’t have to establish tonality or meter at the outset of the LSA, and you don’t have to sing or chant with syllables. The series of patterns itself reveals the tonal or metrical context.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

What do these dialogues show? First, the two words get at basically the same thing: the chain of patterns reveals the context. Second, no term explains itself! No matter what term you use — “partial synthesis,” “chaining,” or “contextualization” — you still must explain what you mean.

Unlike “chaining,” the word “contextualization” brings with it a great disadvantage: it’s a bloated, academic-sounding, 7-syllable monster that will frighten newcomers. (And I should add that it’s an aberration for Andy Mullen, whose prose style on his website is always clear, straightforward, fun, and engaging, as you’ll see when you read his material at https://theimprovingmusician.com/.)

In general, music teachers are turned off to Gordon’s MLT — and this has been the case for more than 40 years — because of the language. Actually I believe the density of the language, not the jargon itself, drives people away.

One immediate way writers can make their prose less densely packed (and more readable) is to go slow when choosing polysyllabic words. In short, MLT writers should think long and hard before they expand perfectly good root-words with needless prefixes and suffixes. The word “audiate,” for instance, is not a problem; but it grows into a problem when we add suffixes to it. What about audiation? Or audiational? Or (heaven help us) audiationally? Do you feel the difference? The more syllables writers stuff into their words, and the more polysyllabic words they cram into their sentences, the more they poison their writing style. (I’m not, by the way, a fan of the suggestion Strunk and White [1999] offer: omit needless words. Omitting needless syllables strikes me as a better way for writers to improve their style.)

But let’s get back to the main thrust of this blogpost: chaining vs. contextualization. To be fair, I’m satisfied with neither term. Why? For the reasons I mentioned above: those words fail to account for how students learn to understand tonal and metrical contexts. In short, those words reveal nothing about how our students learn to compress music into series of patterns.

In Part 3, the final installment, I’ll show with musical examples how chaining/compressing works in practice.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

PS. In each of my posts, I aim for a Flesch Reading-Ease score in the low 60s, with an average sentence length fewer than 17 words, and an average word length of roughly 1.5 syllables per word.

Flesch constructed his readability test so that the average word length and the average sentence length interact. I knew this post would be shot through with polysyllabic words; so I compensated for that sad fact by splitting sentences whenever I could, and by truncating gratuitously tautological and grandiloquent polysyllabic linguistic units — pardon me, by hacking away at syllables until only the roots of words were left.

The average sentence length of this post is 14 words per sentence, and the average word length is 1.56 syllables per word.

This post has a Flesch Reading-Ease score of 63 (placing it on an 8th grade reading level).

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Bluestine, Eric. 2000. The ways children learn music: An introduction and practical guide to music learning theory. Chicago: GIA.

Flesch, Rudolf. 1951. How To Test Readability. New York: Harper & Brothers.

Gagne, Robert M. 1965. The Conditions of Learning. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Mullen, Andrew: https://theimprovingmusician.com/

Strunk, W. and White, E. B. 1999. The Elements of Style. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

[i] https://theimprovingmusician.com/partial-synthesis-the-enigma-of-the-skill-learning-sequence-part-1/